In the early months of 1962, Neil Armstrong was wrestling with a decision: stick with flying experimental aircraft like the rocket-powered X-15, which flirted with the edge of the atmosphere, or apply for a chance at becoming an actual astronaut.

At the time, test pilots like Armstrong didn’t necessarily think the fledgling space program was the way to go. They were doing serious, challenging work, taking aircraft to ever newer extremes. And would astronauts even be pilots? NASA, now marking its 60th anniversary, first envisioned them as mere passengers and test subjects.

Armstrong knew, too, that aerospace R&D projects didn’t always pan out.

He had a good thing going: ‘The X-15 program was real,’ Armstrong told biographer James Hansen years later. ‘You knew it was real.’

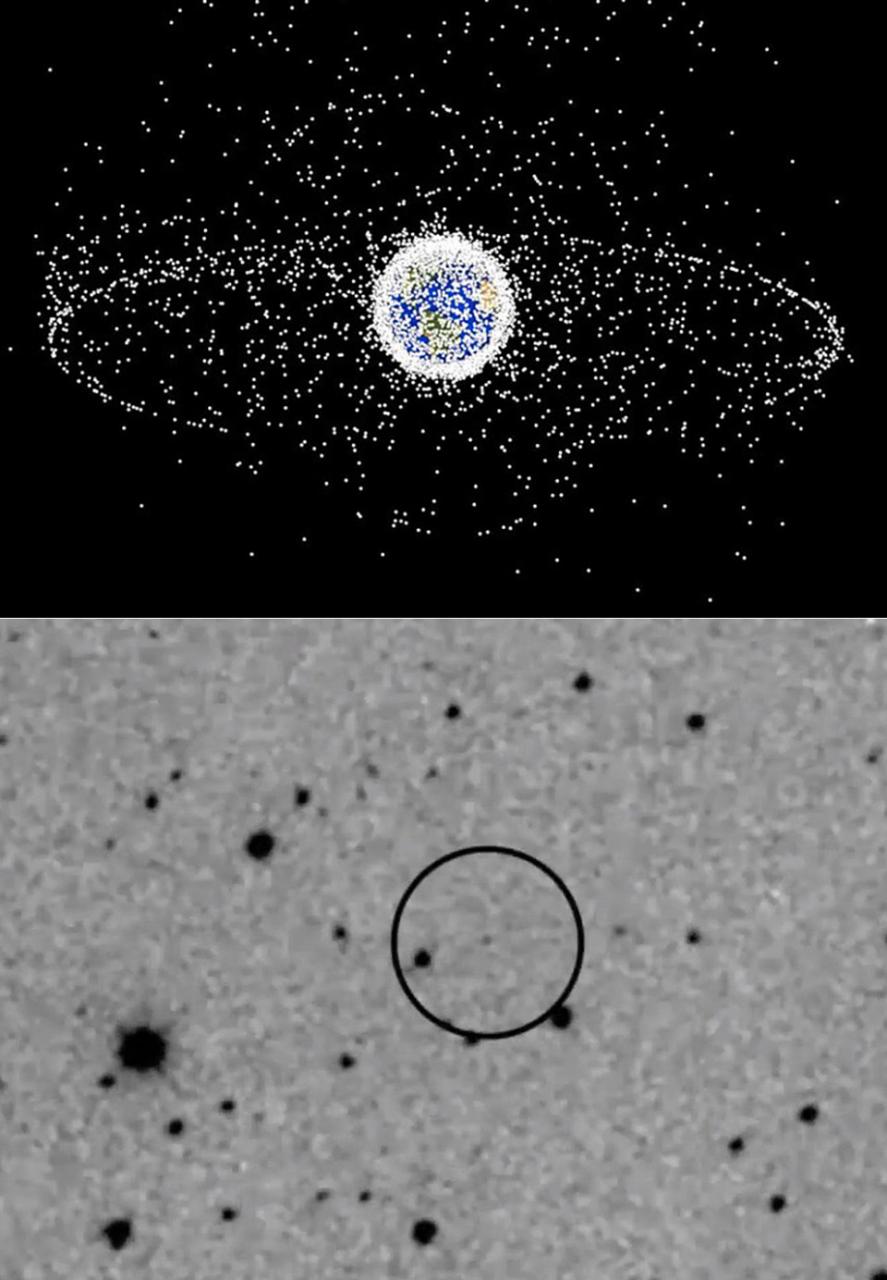

This is a tale of NASA’s early years. The space agency was born on Oct. 1, 1958, a year after the Soviet Union — America’s Cold War nemesis — had sent Sputnik, the first satellite, into orbit. Six months later, it introduced the Mercury Seven astronauts, including Alan Shepard and John Glenn, who would follow Russia’s Yuri Gagarin as the first humans in space.

Even as NASA was still staging PR events with the Mercury astronauts, it was separately starting to test the boundaries of space, the mechanics of spaceflight and the tolerances of human and aircraft performance with the X-15 rocket plane.

Little remembered today, NASA’s X-15 program provided information that would be vital to the early manned spaceflight missions, including Apollo, and that helped set the stage for the space shuttles that started flying two decades later. In fact, if it weren’t for the hand-wringing in Washington over Sputnik, the rocket plane method might have been how we put people into orbit in the first place.

‘The original concept was, we’re going to incrementally learn what we need to know, and something like the X-15, that’s going to be how we’re going to get into space,’ said Hansen, author of the Armstrong biography First Man, on which the upcoming film is based.

But ‘incrementally’ lost out. A sense of urgency had overtaken Congress and the country in the aftermath of the October 1957 Sputnik launch, and it wouldn’t let up for years. NASA was created to conduct ‘research into problems of flight within and outside the Earth’s atmosphere.’ The work being done on rockets became a national priority. Rocket launches were big news.

Before too long, NASA would take on iconic status, a symbol of America’s scientific prowess and can-do spirit. Its astronauts became heroes, devotedly portrayed in Life magazine cover stories and recipients of ticker tape parades.

Even today, as NASA grapples with a much different world — American astronauts have been riding Russian rockets to and from the International Space Station, while private companies like SpaceX shuttle cargo into orbit and make plans for journeys to the moon — it retains the luster from those early achievements.

‘A true space vehicle’

And what an achievement the X-15 was, even if it’s since become a footnote in the national consciousness.

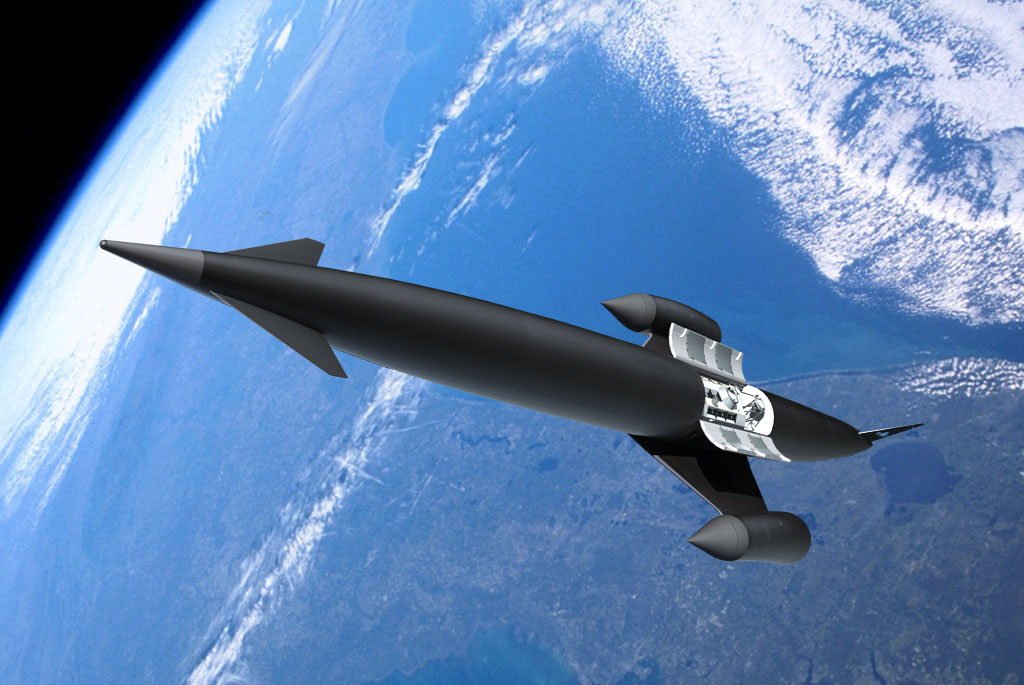

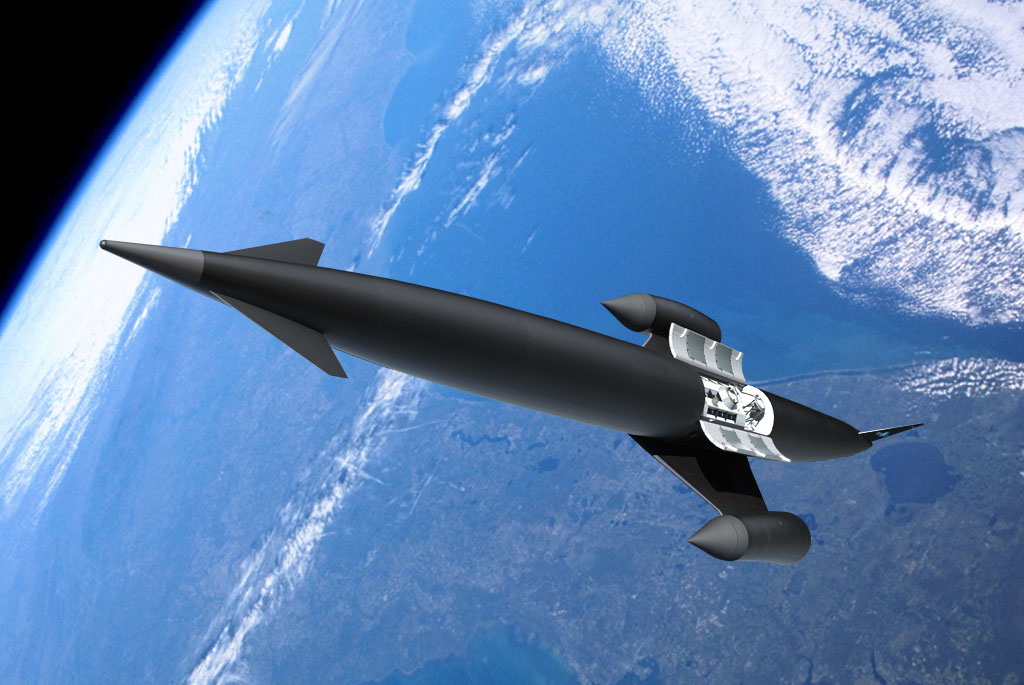

The X-15 was one of the most powerful aircraft ever built. Conjured up several years after Chuck Yeager and the X-1 broke the sound barrier in 1947 and ushered in the era of supersonic flight, the X-15 was designed to probe the realms of hypersonic flight, approaching and even exceeding Mach 5, or five times the speed of sound.

Preliminary designs even suggested that an X-15B (which in the end never got built) would be capable of exiting the atmosphere, orbiting the Earth at least three times and then re-entering the atmosphere for an aircraft-like landing.

‘The rollout of the X-15 marks the beginning of man’s most advanced assault on space,’ said Harrison Storms, the plane’s chief engineer at manufacturer North American Aviation, when the X-15 made its public debut on Oct. 15, 1958. ‘In the X-15 we have all of the elements and most of the problems of a true space vehicle.’

The biggest problem with space vehicles? No one anywhere in the world had any experience in that area. Pretty much everything was still theoretical. The US and the Soviet Union at this point had made only a few rocket launches to put small, primitive satellites into orbit, and it would be two and a half years still until the first, brief manned missions into space.

At this point, it was all still so much trial and error.

And the X-15 was very much an experimental aircraft (that’s what makes it an X-Plane). It was a joint project of the National Advisory Council on Aeronautics — the four-decade-old agency that, in effect, became NASA, and that had begun initial work on spaceflight problems around 1952 — along with the US Air Force, the US Navy and North American Aviation, a private company.

It wasn’t an elegant-looking aircraft, with short stubby wings, a little bump of a one-man cockpit and a 50-foot fuselage that barely expanded upon the tube that held its rocket engine. It was built for sheer straight-line speed.

Its performance would allow engineers to investigate things like stability and control at extreme speeds, and the intense heating that would occur. To conserve fuel, it wouldn’t launch itself from the ground. Instead, it blasted off from a B-52 at about 45,000 feet before igniting its rocket engine for 80 to 120 seconds for a flight that would last around 10 minutes.

When it crested outside the atmosphere, the X-15 would use little thruster rockets on its nose and wings for control, since normal aircraft controls wouldn’t work at those altitudes. Those controls were novel then, but they would become customary on spacecraft.

What sets test pilots apart

Don’t think of test pilots as cowboys in the sky. For all their daring, their willingness to make flights that could turn fatal in an instant, they’re serious about their work and about reducing risks.

‘The thing that sets test pilots apart from other pilots is a decidedly methodical, engineering approach,’ said Cmdr. Glenn Rioux, commanding officer of the US Naval Test Pilot School in Patuxent River, Maryland, one of only a handful such programs in the world. Over several decades, 87 of the school’s graduates have gone on to NASA’s astronaut program.

That temperament was certainly true of Armstrong, who had flown combat missions in the Korean War before joining the NACA. ‘Foremost in his mind he was an aeronautical engineer,’ Hansen said.

The first X-15 flight took place June 8, 1959, piloted by the accomplished Scott Crossfield, who’d already made more than 100 flights in rocket-powered aircraft in the Southern California skies around Edwards Air Force Base, where NASA’s Flight Research Center (now named after Armstrong) is located.

That was just two months after NASA announced the names of the Mercury Seven astronauts (themselves also test pilots). In the coming months, the Mercury and X-15 programs would proceed on their separate tracks, the rocket plane flying steadily faster and higher. The Mercury program, meanwhile, experienced a string of delays and well-publicized rocket launch failures.

‘Press interest in the X-15 had become tremendous, because it was the country’s sole existing ‘spaceship’,’ Tom Wolfe wrote in The Right Stuff, which chronicles NASA’s early years and was adapted into a 1983 movie starring Ed Harris, Sam Shepard and Dennis Quaid. ‘Project Mercury, the human cannonball approach, looked like a Larry Lightbulb scheme, and it gave off the funk of panic.’

X-15 versus Mercury

So what happened?

For all the progress the X-15 was making, for all its excellence as an engineering project, it had a long timeline for getting into space. The proposed X-15B, with its more powerful engine, had given way to the planned X-20 Dyna-Soar, a craft under development at Boeing that looked like a race car version of the space shuttle, with the expectation that it would be ready to go in November 1964. (And with Armstrong named as one of six pilot-engineers.)

But Washington was in a hurry.

And for all the failures of NASA’s early, underpowered rockets, they still offered the tantalizing possibility of being good enough for the moment.

‘The politics of the space race demanded a small manned vehicle as soon as possible with existing rocket power,’ Wolfe wrote.

So work on Mercury progressed. As it did for the X-15 program.

In November 1960, Armstrong — clad in his pressure suit, squashed into the cockpit of what he called ‘a real different machine’ — had his first flight in an X-15 after five years as a research test pilot for NASA and its predecessor. (Eventually he’d make a total of seven X-15 flights.) It was a ‘high-tension’ moment, he said. ‘Everybody else has been able to handle it, so you ought to be able to.’

He didn’t — yet — feel the allure of being an astronaut, and Hansen, his biographer, wrote that Armstrong expected he’d eventually become the X-15 chief pilot.

Even as Mercury logged its first suborbital flights, Armstrong told Hansen, ‘we were far more involved in spaceflight research than the Mercury program.’

But it was the Mercury astronauts, anointed by Life magazine and championed by President Kennedy, who were famous, who were heroes even before they lifted off. Especially John Glenn, who in February 1962, in the second manned Mercury flight, became the first American to go into Earth’s orbit.

After Mercury came Gemini — astronauts made spacewalks and performed the first docking (Armstrong again) between two spacecraft. After that, Apollo and the moon landings. Astronauts performed truly remarkable deeds. They were enshrined in national memory and provided pop culture inspiration for everything from David Bowie’s Space Oddity to the Planet of the Apes movies and Marvel’s Fantastic Four.

What the X-15 accomplished

Meanwhile, the X-15 program endured.

Between June 1959 and October 1968, a dozen pilots made a total of 199 flights in one or another of the three X-15 aircraft. Some of them flew, briefly, above an altitude of 50 miles, at which point they could say they’d been into space. In August 1963, NASA pilot Joe Walker got to 354,200 feet, or 67 miles.

As early as June 1961, a month after Alan Shepard became the first American in space, Air Force pilot Bob White had zoomed to Mach 5.27 in an X-15. In October 1967, Air Force pilot Pete Knight hit Mach 6.7.

While those feats are breathtaking, the X-15 flights also provided a wealth of knowledge to aerospace engineers, from the first use of thrusters to data on aircraft behavior in hypersonic flight to the development of the first practical full-pressure suit.

‘In many ways, the X-15 program signaled a shift to the research, development and management functions that characterized the NASA organization soon to come,’ wrote aerospace historian Roger BIlstein.

Now, six decades on, NASA continues to work with X-Planes, including the new X-59, due to fly in 2021. The goal of that project is to see if supersonic planes can make less noise as they break the sound barrier. NASA’s also working on the new Space Launch System rocket and Orion crew capsule in a push to the moon and Mars.

And that means there might be some tough choices for those thinking about whether to fly planes or spaceships, just as there were in Armstrong’s day.

‘I happened to pick one that was a winning horse,’ he told Hansen. ‘Apollo was just so overpoweringly exciting.’